in words, sketches

and music

as recorded by

andrew sterling

as recorded by

andrew sterling

I hope, of course, this site will be found to be deeply affirming. But if not, then I suspect it will challenge.

Have a look round and respond if you wish (see 'blog' page).

I hope it will be used randomly and dipped into, including within each area - it’s the way I work: intuitively. It is hoped this will be the means by which a whole perspective builds. The ‘welcome tree’ represents this approach, the different areas being part of the whole.

(A ‘whole picture’ perspective understands that contemporary crises stem from disconnectedness and incoherence of life today).

The site is being updated, added to and edited regularly: revisit to find new and changed content. (Follow-up material is posted on https://andrewdsterling.wordpress.com/)

(Please note all website content is copyright: please contact me if you want use of any material).

A greater fluency in musical improvising and extemporising (particularly as a teenage church organist) took over a certain ability in art. Won regional composing competition judged by Michael Tippett. Graduate of the Guildhall School of Music (1968). Double scholarship in composition and piano. Studied with Edmund Rubbra, French Government scholarship to the Paris Conservatiore (1969). Studied composition with Olivier Messiaen. Worked with the Quaker International Centre during the Paris riots.

Help set up residents association on new Brixton housing estate (1971) and formed my first multi-style band. Freelance musician employing extemporising and reading abilities - accompanying, recording, conducting, arranging, ballet repetiteur, private functions. Lived on boats for 27 years. Prefer motorbikes to cars (currently BMW R1200RT towing a trailer). Created a number of concert ensembles to play a range of music, including originals, some sponsored by the lottery, local councils and the Arts Council. Concerts in theatres, universities, my own barge, Jubillee Hall Aldeburgh, Cafe Consort (Royal Albert Hall). Currently engaged in solo performances and recording. (fuller biog. details on the performance site click here).

Site designed by www.rd3creative.com, developed by http://codetrix.co.uk/

Reading it builds the perspective out of which the other activities have resulted. Its loose stucture, like jottings in a scrapbook, itself expresses that perspective which builds just by randomly dipping into it. Yet it is also built to be read linearly which progressively builds up the same picture and outlook.

Read More...Do animals tussle with issues of faith, belief and morals? Or do they just get on with their purpose in life anyway? It is us who have the need to judge their lives, often as being mean and red in tooth and claw - when one would assume they don't have a similar need to judge us - albeit we are aren't short of such qualities ourselves alongside our mountains of beliefs and morals.

Read More...FAITH AND BELIEF.

Does it necessarily follow that having a belief is having a faith?

Searching the web finds various explanations of ‘faith’. One suggestion is that it’s the trust we all experience as babies not to be dropped by a parent, another that it’s a firm belief in something for which there may be no tangible evidence, whereas a third stated that real faith is in any promise made by God as it is impossible for God to lie.

Such explanations would seem to be subject to failures of expectation and so perhaps arise from anxiety rather than as expressions of faith.

I wondered what various religions would define as faith, so I turned to the BBC Religions website which outlines Hinduism, Baha’i, Buddhism, Jainism, Mormonism, Paganism, Rastifari, Shinto, Spiritualism, Taoism, Zoroastrianism and Sikhism, Atheism as well as the three Abrahamic faiths.

What I found were descriptions of beliefs, concepts, practices and narratives, most of it occupied with mostly ancient extra-natural or paranormal events, documents and persons, with very little about what faith itself might be, as against believing these things to be true or real. It would seem from this that such Faiths are about identity and culture. Which would be why it’s such an emotive area, as we all too often can see and experience.

Yet having beliefs and concepts are not exactly avoidable. My faith, for example, involves being able to be inclusive of people rather than to reject - yet even that, as a statement, as words, immediately appears as belief which demands to be lived by, yard sticks by which to judge oneself and very likely, others. So, when put into words, a note of negativism is introduced in an instant. So faith is not in words and ideas but in a sense of...what?

This first became clear for me around the death of my father when it struck me that whatever one believes about death, belief is about what one wants. That’s not going to change the actual phenomenon and whatever the reality of death is - just for us! Whatever happens at death, happens anyway, and it is the right thing, because it’s life. So, it was clear; stop wanting to make it up, let it go, relax, and.. have.. faith.

Yet here I am using words in an attempt to communicate an experience of faith which is not about words, concepts and thought. So I have tried to encapsulate this by contrasting belief and faith:

Faith is in the absence of beliefs and dogma.

Dogma and beliefs are the absence of faith.

Faith has no name or terms and concepts. Beliefs have names and terms and concepts.

Faith implicitly accepts. Belief implicitly excludes.

Faith is not about being right or wrong. Belief leads to the implication, at least, that other beliefs are wrong.

Faith is about letting go and letting be. Belief controls.

Faith embraces. Beliefs conflict.

Faith opens up. Belief ties down.

Belief presents own agendas as truth. Faith has no agenda.

Belief is make-belief.

Interestingly this for me has brought to life Jesus’ references to faith - in a nutshell, to drop the worry; have faith, in ourselves, in each other and life. Unfortunately this personal and shared inner freedom subsequently became words, fixed concepts and the tool of the many variants of the controlling, beliefs-ridden, church. Much like other belief-based religion.

Is education or learning skills inherently a good thing for the student, or is it really for the social context within which the student has to, at least, survive? Never has human society been so vastly developed in knowledge and skills, but is it more content or more fractious, than say, simple tribal life? Who is it really for?

But if one is to learn a skill - and in today's society, that is inevitable - then how much should be imposed or should come from, and in effect, be directed by, the pupil/student?

While this teaching section is focused on learning to play the piano, it directly relates to these questions.

Read More...While this section is about teaching a musical instrument, specifically the piano, it concerns itself with the the central matter of how humans learn which applies to all education. Part one therefore considers the critical nature of the educator's attitudes. Following on from that Part two outlines how this is realised in an uncommon, common sense approach to piano playing.

Part 1: TEACHING AND THE EDUCATOR'S VIEW ON HUMAN NATURE

Which is nearer to the reality of how humans work?

1. They intuitively know before being made aware

2. They know it when they see it

3. They know nothing so need filling in with knowledge

4. They are nothing and need moulding and shaping

5. They don’t want to know and need forcing into it

6. Perhaps a bit of all 5 - with an emphasis on one end of this spectrum than another.

For example, they may know nothing but suddenly they know it when they see it. Or they don’t want to know and need forcing into it only to discover they intuitively knew while being moulded and shaped. Or how about they are nothing, don’t want to know, so need forcing into it by being moulded and shaped so that they then know it when they see it?

Or perhaps each statement is a description of different people and at different stages of their learning.

Certainly overall fashion and belief in education has wandered back and forth over these outlooks, each one eventually having had its day, is then found to be wanting, so leading to calls for either liberalising or toughening up - depending where the zeitgeist was heading.

It depends on those in education think it is for. Rarely is this questioned because, well, that is rather dodgy - it feels like questioning the purpose of society, its economy, and therefore of our own lives’ purpose within it. To question the whole caboodle always gets to sound bonkers and extreme, yet it’s vacant not to.

So perhaps the questions above arise from what is being required, rather than being competing descriptions of human nature. For example, if education is more about providing personnel to fill jobs within the economy, then it’s more likely students will be regarded as needing moulding and filled with relevant knowledge. In that case, the driving force comes from the educators, and behind them, government targets. If, on the other end of the scale, if education is primarily seen as a way in which the person can feel fulfilled, then the focus, and the drive, will be on providing an opportunity for pupils to find what they already have and to allow/encourage it out.

Of course, some brains lean more towards the first and some the latter anyway, so whatever the education criterion may be at any one time certain kinds of thinking and learning styles will fit in and be encouraged more than others. Indeed someone can have a great ability of some kind but will feel unable to function if it doesn’t relate to the approach being assumed by the educational approach pertaining at the time. Then low self regard will also become a big factor, and that itself stymies inherent ability. But importantly, it will have a greater impact on those with a pronounced talent/awareness in a particular field just because it is of instinctive importance to them. They will feel they are particularly lacking ability because they are unable to meet what is expected of them, and in what way it is expected.

Narrow definitions and expectations of ability also give rise to what I term ‘ability pyramids’ (see ‘Relax, It Doesn’t Matter, page 14). In other words, whatever the criterion is (by which to judge ability) - and even however trivial (it isn’t a matter of how clever and important the criteria are) - a relatively few will meet it and increasingly more will be unable to meet or approximate to it.

Judging ability by some fixed idea of ability is therefore illusory, and it is an illusion to serve those who have the need to make judgements, not those who are judged. While it will bring out those most able to meet the criterion, it will exclude most, including those who would have otherwise blossomed in whatever field they are gifted in, in ways that the educators cannot, by definition, imagine themselves.

Educators not only need to be void of their agendas in education, but to be watchers and listeners, so that they are able to gradually perceive whatever kind of brain (ways of thinking and working and engaging) the student might have - be they intuitive or need filling in with knowledge, or one of the permutations in between. Anything else is ideology and idealistic. This is a dynamic in which, on one side, the intuitive are ready to receive knowledge once their intuition is allowed free rein, while on the other, the knowledge-able person will begin to see dynamic relationships between the facts.

It would then follow that a student who apparently doesn’t want to know, and has to be forced, is probably failing to be something he/she is not, rather than failing per se - like a rose failing for not making it as a tulip, so to speak.

PART 2: TEACHING THE PIANO

Introduction.

There is overwhelming mythology surrounding the ability to play an instrument, especially in the classical field. Someone who can play exceptionally well is viewed in a semi-supernatural aura. If you don’t know how someone does something, especially in the arts, it’s magic. All part of creating the worshiping of icons upon which much of the modern - including the cultural - economy depends.

But it is destructive.

While most activities require talent they also need technical know how, and that includes the arts. Or, as one might put it, they need the inspirational and the mechanical. Given the over-bearing mythological coating of the arts much of apparent teaching is about the mythology, not about common sense skilling. A student will be as much caught up in that fantasy world as anyone else.

In consequence, much of a teacher’s time - whether they know it or not - is about being faced with the psychological and emotional problems students have about their playing, but in reality, about themselves. The fear is that if they play badly - as they will see it - they are giving away that they are not only rubbish musically but a rubbish person too. They see playing as the ultimate exposure of what damning negatives they feel about themselves while being heavily engaged in trying not to believe it. So they turn up to a lesson full of trepidation trying to be perfect. This is almost a definition of setting things up to fail, but they will also be hating the whole thing anyway.

What’s that all about!? Why engage with something which is supposed to express you but you are full of fear and hate?? But trying to be socially successful, in the cultural fantasy world, is what it’s all about. Their fantasy of playing well, and of a child’s parents, and of showing the world round them how clever they are (fed by the media myths of glory of performers, writers and composers), drive them on until they can’t take it any more and give up.

So this is what I found works to counteract this destructive fantasy land and instead gets a pupil/student to learn to let go and enjoy themselves:

Children

For those children, who - for the above reasons - just cannot engage with a keyboard, do not try to instruct them at all. I was engaged by a parent to try and teach her young daughter of six who couldn’t even face the piano, let alone touch the keys. I could see that she was ravaged by a fear of failing to meet whatever it might be. I never did find out why the mother wanted her daughter to learn, and she asked me if I wanted to carry on trying. I felt I should try. So I dropped all pretence of instruction and instead plonked my hands on the piano, making sounds that she might like to describe, or say what they were like. It wasn’t long before she turned round to see if she could make up sounds that reminded her of something - an animal or something. This gave her something that belonged to her, and not failing some expectation from the teacher (me in this case). This eventually led to my being able to suggest she picks up any fingers while holding her hand down on the keyboard, with the result we got a chord. And by moving up and down the keys we could make the chord walk up and down. Sounded like music - and what did the music make her feel or make her think of? This in turn led to other chords, and then I could show her how a tune could be made out of the chords. Wasn’t too long before she was coming back with all sorts of tunes of her own which I wrote down for her, with her mother saying she never stops playing! It’s because it belonged to her - she set the agenda of the lesson each time, and was filling her self with herself and with delight (and me and her mother too!). When she moved up to the next school she also moved onto ‘proper’ piano lessons at the school.

But that is not a prescription. I never did ‘apply’ that technique to anyone else. But I always looked for what it was in the student that turned them from their negative to their positive. The principle is that you are there to enable the child to find what and how they do things. My task was to see a direction they can’t see (because they are living in the experience of the moment) and to present possibilities from that that might engage their imaginations, for themselves, not for me.

Adults and young people

What is important to remember here is that many adults too are equally screwed up by the magic myths they absorb from the social context. They too need to make piano playing theirs. But the process towards this is very different to that of children.

Many older students and adults turn to piano lessons because they are ‘stuck’. This is usually due to some childhood lessons that they found perfunctory and/or scary, but have tried to carry on, on their own. As they generally had a downer on themselves when it comes to piano playing, they just want to sound ‘good’. This means they have got into all sorts of ‘habit ruts’ - trying to sound good by using cliches repeatedly, but in one way or another, sounding vague or ‘blurred’, tripping up in the same way or same places. They basically want some magic to get what they are doing sounding classier. But that is like asking to put a shiny coat of paint over a rust bucket - it’s not going to happen. Their playing is intrinsically one bag of faults, beyond repair - not that I say any of that; they don’t feel that good already.....

But this is where the mechanics of playing come in. I initially focused on convincing them it’s not all about talent but about knowing what you are doing. Having established they played by luck and habit, I would begin to put over that playing is a mechanical skill. This would be revolutionary to them. I used similes to explain. Do you, I would ask, learn to drive a car because of a talent, or do you start by understanding what does what, when and why - with the pedals, gear stick, brakes etc? Or do you really think if you have an initial natural talent for driving - and indeed some people turn out to have such a thing - that you can just jump in a car for the first time and off you go, all fluent and in control?

And so, when it comes to piano playing, I would ask them to forget the mythology of talent and focus on with how to learn to 'drive a piano'! It is but a skill, as anything is. And because the mind is focused on common sense and not on the cobweb of self-doubting fear, it would enable whatever talent is there come out and fire up of its own accord.

If they are convinced - and willing in effect to start again, I would then set about teaching what these mechanics are.

THE MECHANICS OF LEARNING

There are 3 parts to the skill of ‘operating’ a piano -

a. hand shapes

b. hand ‘ballet’

c. hand exercising

1. Hand shapes. In the initial instance this means the basic forms of triad chords. These not only form the backbone of western music, but are therefore the backbone of the hand shapes of piano playing (and these shapes replicate in most keys):

Plus the equivalent in the left hand.

One learns the precise feel of the spacing of the fingers so that one can actually pre-form them in the hand away from the keys and then place the hand 'blind' on the keys with the result that the right notes will play.

Get used to them: keep the hand shape and play it up and down the keyboard. Make up a piece doing this. Then do so using the different shapes in different places. Play the notes singly using the left hand to play the chords you are playing over. You are then making up tunes of your own - and practising at the same time.

2. ‘Hand Ballet’

This is finding out and learning what the movements are that the hand has to perform to move between the hand shapes. This could, of course, include (what most students are wont to do) just taking a leap in the dark with the hope that the hand lands up on the right notes (and when it does the student takes from that they must have learned it. It’s mindless faith in magic).

But learning the movements of one hand shape from one place to perhaps another hand shape in another place, is to learn to play with certainty. In fact one could say that learning a piece is not about notes but about learning what happens between the notes: the right notes being the result.

So, in the case of the first 2 right hand chords (as above), either one could stretch out the little finger from the G and learn to judge the distance where the top C is and then form the rest of the hand shape you have learnt underneath. Or, using the middle finger, guide the thumb onto the E of bar 2 and then space the other fingers round that according to the shape you have learnt for that chord.

There's often several ways of working out what hand shapes and movements enable the hand to reach notes with certainty - without looking (see below - ‘playing is tactile’).

And it’s marvellous - because they each directly reflect the other as the same pattern, aurally, on paper, and in the hand. Awareness of sound patterns ties up with how they feel physically and how they both look on the ‘graph’ - ie manuscript - paper. So, the manuscript version is the graph of what the hand does, and what the ear hears. They are all one and the same thing.

So, in the case of the above triad positions, the first chord, the ‘root position’, is a closed hand position, with the notes evenly spaced - in the hand, as in the music, and as in the ear. The second chord, the ‘1st inversion’ has a characteristic spacing on paper, as it has in the hand and as it has in the ear. And so on.

The result is that as you progress in ‘hand ballet’ you recognise and become increasingly familiar with the fact that music is built from repeatedly-used ‘building blocks’, you find your sight reading improves massively as a result - you recognise the patterns - along with your sense of hand and finger accuracy. You have got used to the shape of the ‘movement language’ and are ‘speaking’ it - ie reading and playing it - with an insiders increasingly fluent understanding. Again, marvellous!

As you see from the above example, I developed a series of signs that indicated the movements between hand shapes and positions which, like ballet ‘notation’, visually indicate the hand actions, and which, along with the musical notes themselves, the pianist would read. As explained, he/she learns and plays, in effect, the gaps between where one lands (on notes, chords etc) as well as the notes. Quite a revelation.

Here is an example of music in which I inscribed the kind of ‘ballet’ movement signs that developed:

But playing is tactile. Don’t look at your fingers!! It’s the fingers that do the playing, not the eyes, and the brain thinks through the fingers, not eyes, or it does not think at all. Eyes do not press the keys, which is why the brain can only tell the fingers vaguely what to do if the info is via vague visual impressions.

The problem is that people initially want quick and easy results and using eyes always seems the short way out. It’s the short route alright - to the longest ever road - of never getting there; it’s the way to vague, inaccurate playing, the consequent building up and the setting-in of bad habits, and of sheer frustration ie being ‘stuck’. Know the feeling?

Ironically the quick way to results is the apparent long road - bothering to be accurate from the start; while the brain is still free from being imprinted with bad habits. However if your playing is subject to these already, then starting anew is the answer. You can’t make good a bag of bad habits.

I refer to practising these shapes and movements as ‘silent playing.‘ For example, passing a 3rd finger over, say, the thumb (right hand) should involve rolling the thumb so that the 3rd finger ‘arrives’ over the note rather than scrambles for it. You can hold the thumb in place and keep passing the 3rd finger over and hover it over the note to be played, and check if it is over it. Repeat until you know for certain.

‘Going Wrong’ - is a massive fear with students, and they tense up for fear of it. But the approach this article outlines gradually obviates that because it is replaced with the attention on how it feels to get to the right note. ‘Going wrong’ then becomes a welcome and vital tool because it is the contrast between hovering over the wrong note (as above - 3rd finger over thumb) which makes the right note distinctly clear.

The great thing also is that by practicing each piece this way the brain and the hand/fingers become very sharply clear on the keys (distances and movements being constantly repeated in music), so that the fingers become more and more automatic in knowing where notes are. Eventually even the signs can largely be dispensed with.

As this matter of fact - one might call ‘mechanistic’ - approach is established it allows the magic of music to be expressed - real magic, one might say, instead of the vague fantasy magic of wishful thinking. Real confidence takes root with it, not bravado ‘confidence’ attempting to cover fear and insecurity when playing.

Exercising

To make these moves with certainty and ease

learn to really focus through your hand on each move and shape, and

know how to stop stiff muscles getting in the way.

Because -

it’s no good just vaguely going through the motions - it’s not the movements and shapes in themselves that does the trick; it’s in meaning every articulation of each move that’s the secret.

Making every move clear in your hand means you are also learning the music and are exercising the muscles in the right way too.

In fact you can extrapolate any physical difficulty in a piece of music and turn it into a very useful exercise - by repeating it and then moving it up or down in some kind of sequence. And it makes what was difficult become easy.

It was my doing precisely that that led me into developing a series of exercises with which I always begin my musical working day.

The general idea behind these series of exercises is to start with waking up the whole hand and then gradually focus on the parts of the hand to refine the articulation.

So, to begin with,

Whole hand stretch.

Don’t over-do these; build it gradually, otherwise you can sprain the muscles. To reach these stretches you will need to angle your hand over the notes you are reaching towards, so that the top of the hand angles from left, then is centered, then faces to the right, so helping place the relevant fingers onto the relevant notes. But again mean it, don’t just do it! The first one is for those who either have bigger hands and/or are pretty well down the piano road.

Excercise 1

(Exercise the hands separately).

The harmonic pattern then is: broken diminished chord -> root chord (and flat 7th) one semi-tone below -> the next diminished chord one tone up ->root chord (and flat 7th) one semi-tone down..... and so on as far as your hand feels it’s OK to go.

As this is a real stretcher for those with a smaller hand width and/or still developing their hand muscles, it could be damaging. So, either build it up carefully or here's Exercise 2:

Exercise 2

Exercise 3

This simply takes the first two quavers of Exercise 2 and carefully and solidly articulates back and forth between them, twice or four times and then, similarly, the 3rd and 4th quavers. This exercise is the halfway point between the hand stretches and those that focus just on fingers.

Exercise 4 is is indeed for the fingers only. An added importance to this one is not to slant the hand itself (as with the above exercises) but keep it level and use only the fingers themselves to play.

etc

This exercise is adaptable to emphasise whichever finger combinations seem to be weaker. The pattern in the left hand could be used for the right hand, and vice versa. Or the notes can be turned into triplets such as (in the first bar for instance) C, F, A and its reverse - A, F, C.

The main thing is to ‘listen’ to your fingers and see which combinations help loosen and sensitise which combinations of fingers.

Wrist flexibility

If wrists are inflexible then they hold back the flexibility of the fingers. So wrists need exercising too.

Either use octaves in each hand ascending and descending in semitones for as far up the scale and back as the current strength of the wrist allows. Again, do not over-extend the range - it can lead to strains.

Or using the harmonic patterns of the exercises above repeat each chord 4 times before moving onto the next chord.

To enable the fingers greater flexibility I use wrist exercises between each finger exercise.

There are many further muscle-loosening exercises, some of which will be published later in this section.

UPDATES TO FOLLOW

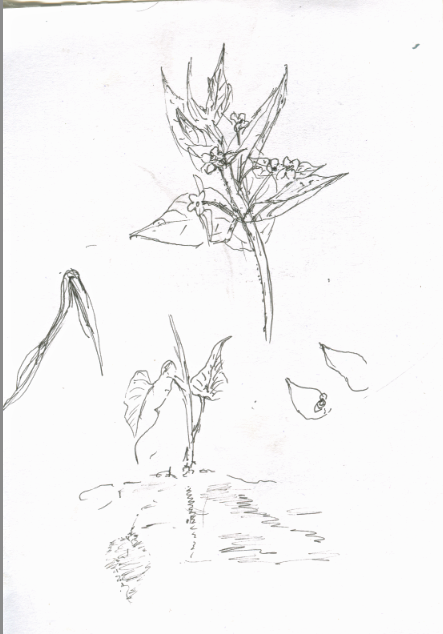

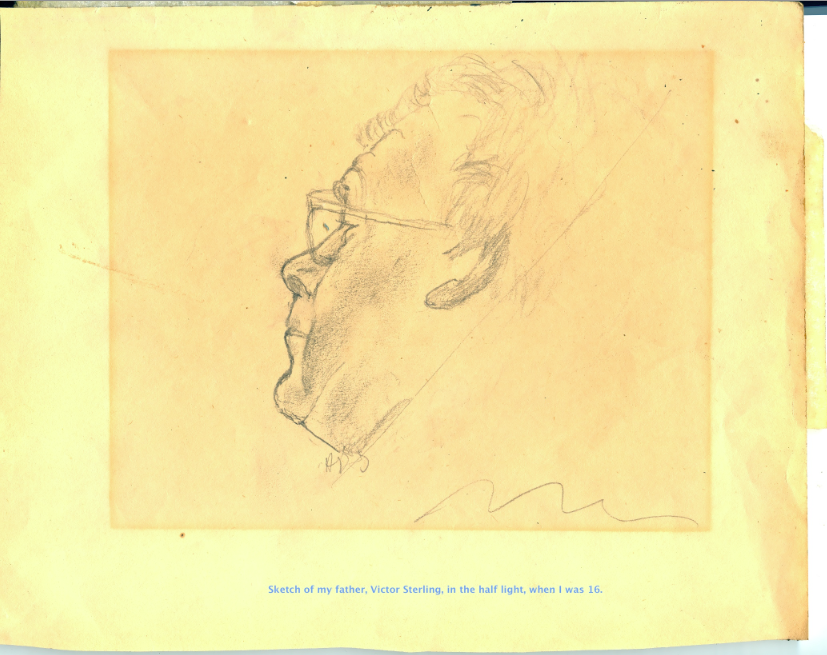

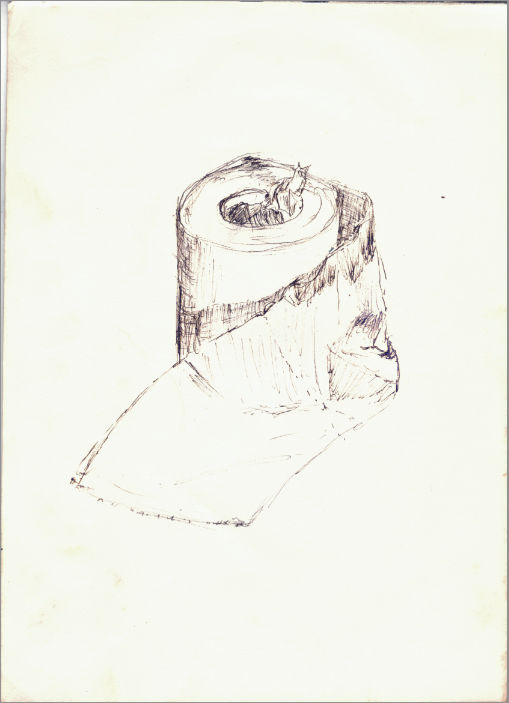

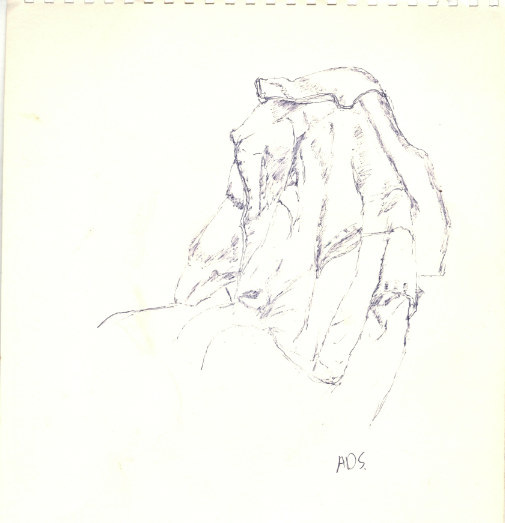

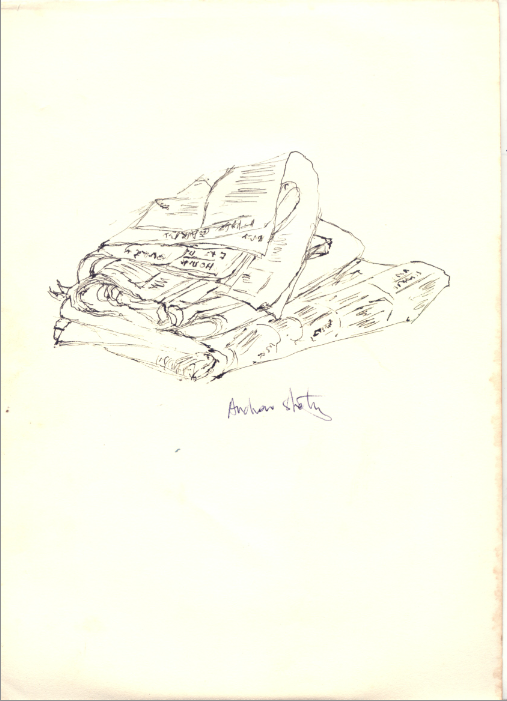

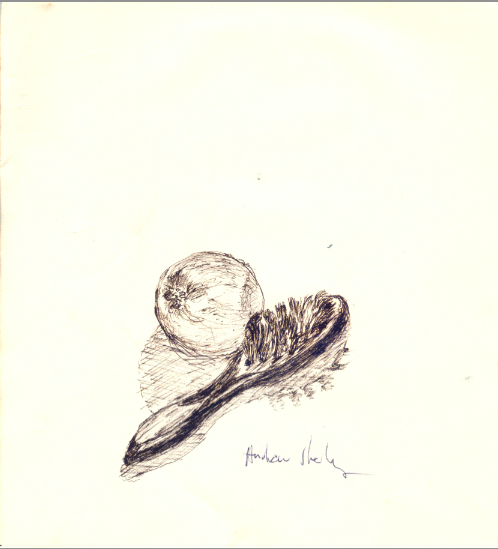

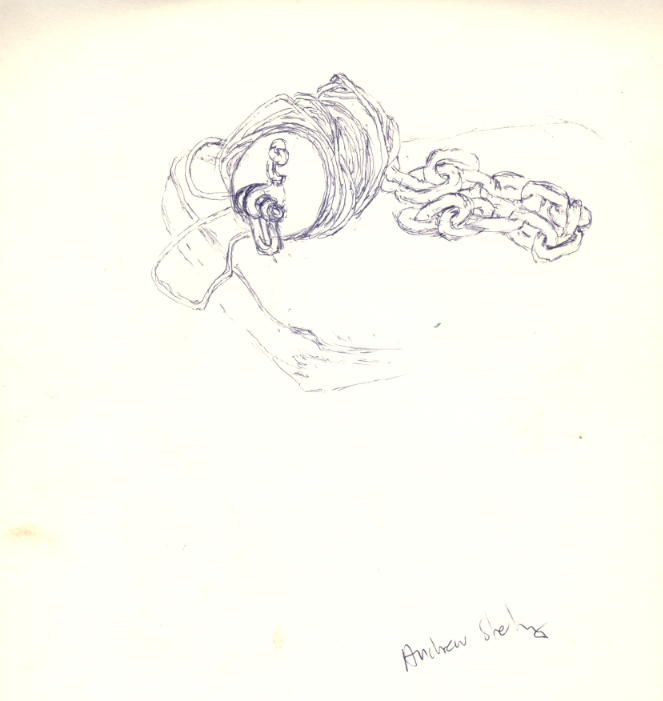

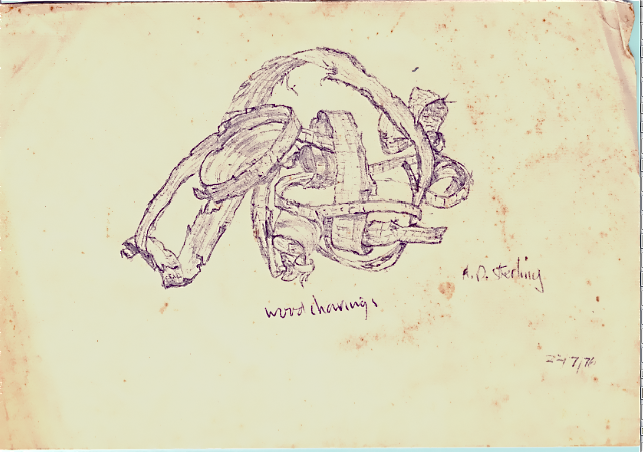

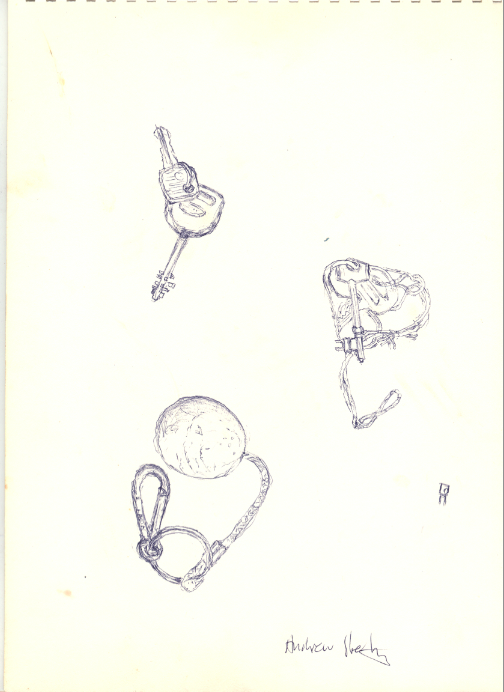

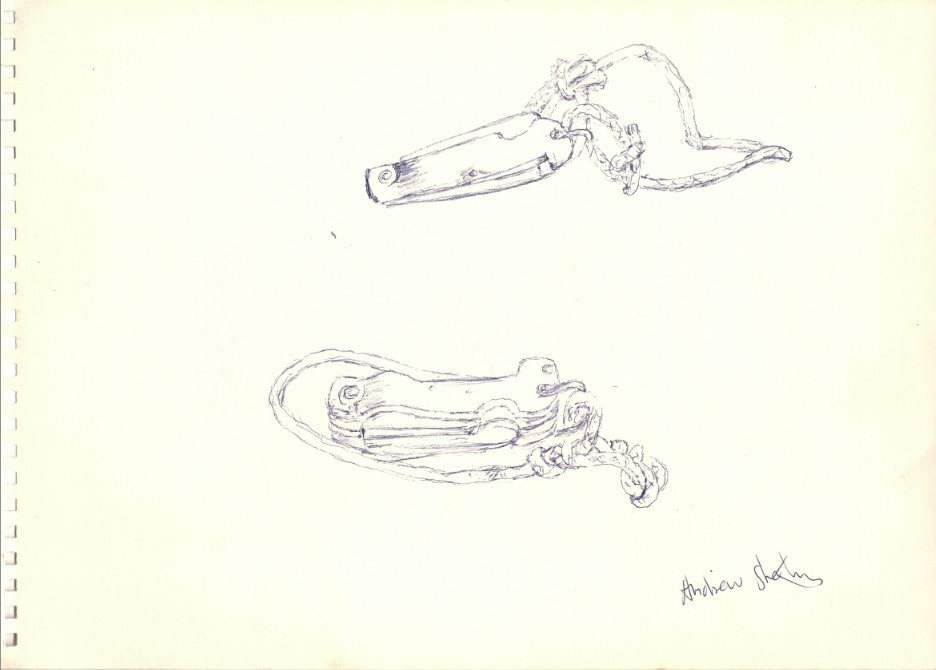

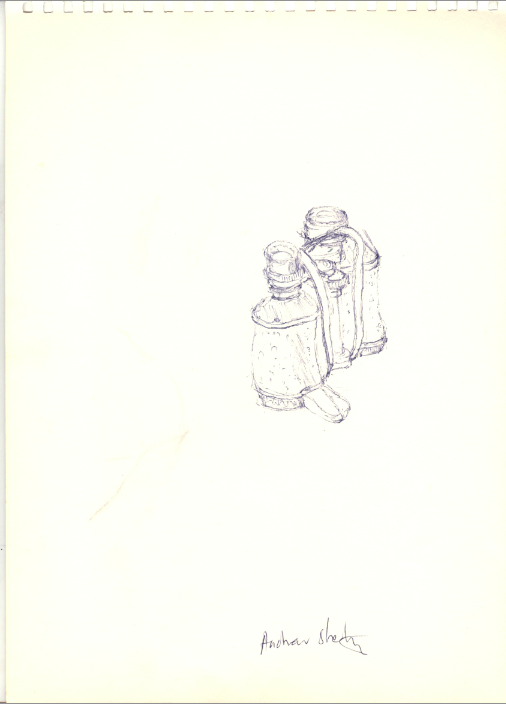

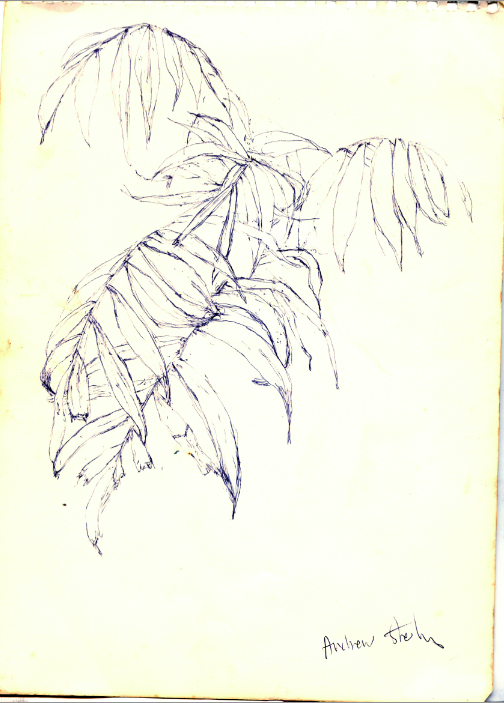

I am a reluctant and limited ‘sketcher’, despite my school art teacher entering me in for my continuing education while specialising in art at Loughborough Art College - but which was overtaken by the music.

But I do have a fascination, both of fine visual art and of the big world of the small scale which I now realise expresses my sense of the realities of the human scale rather than the small world of the grand and grandiose.

This, I think, is probably being reflected in sketching objects or parts of objects. For some reason my favourite medium is the ballpoint pen.

Name of image Tools

Name of image Foggy the cat, 2

Name of image Leaves

Name of image Young Anna

Name of image Tilley lamp

Name of image Sketch of my father, drawn in a tent when I was 16

Name of image Old piano stool

Name of image Bog roll

Name of image Quiltered jacket

Name of image Foggy the cat, 1

Name of image jumbly jacket

Name of image Pile of newspapers

Name of image Natural bedfellows

Name of image Flying jib bits

Name of image My motorcycle boots

Name of image Bathroom stuff

Name of image Painting of my father, 1968

Name of image Hanging raincoat

Name of image Bottle screw and block

Name of image Canadian fence

Name of image Alarm clock

Name of image Coal scuttle and keys

Name of image Wood shavings

Name of image Oddments

Name of image Oddments 2

Name of image Keys

Name of image Old penknives

Name of image Bins

Name of image Plant

Name of image Warped antique

Name of image Knobbly plant

Name of image Kitchen brushes